His admirable personal qualities couldn’t mask his failure to lead, leaving a presidency widely regarded as ineffective

For interview requests, click here

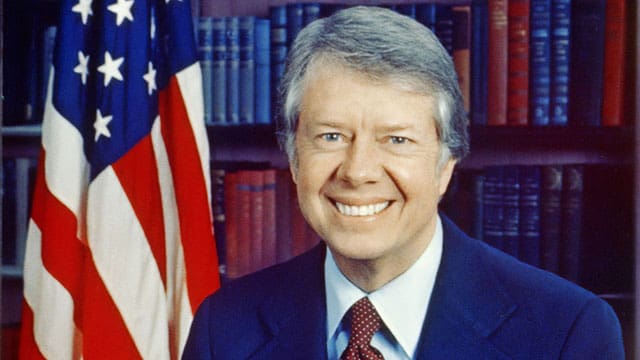

Jimmy Carter, the 39th American president, was in his 101st year of life when he died on Dec. 29, 2024. The fulsome tributes invariably acknowledge that he was smart, well-intentioned, hard-working and detail-oriented. And while Carter was also prissy, self-righteous and sometimes petty, there’s little to quibble with in that assessment of his virtues.

But, as I argued in a February 2023 column, Carter was always an accidental president, someone whose rise to the pinnacle was facilitated by an unusual combination of external events. And four years after his 1976 triumph, his re-election bid crashed and burned in a humiliating landslide defeat at the hands of Ronald Reagan.

Almost from the get-go, Carter had troubles.

In Washington’s world of separated powers and big egos, he had difficulty persuading or bending others to his will. There was also a mismatch on fiscal matters between him and powerful players in his own Democratic party. Although he cared about deficits, spending was their natural disposition.

Jimmy Carter was an accidental President |

| Recommended |

| Jimmy Carter wasn’t a great President, but he was a good man

|

| Covering up U.S. Presidents’ illnesses is nothing new

|

| Can Kemi Badenoch become Britain’s first black prime minister?

|

Stir in double-digit inflation, rising unemployment, and foreign policy shocks like the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Iranian hostage crisis, and you were left with a man who seemed overwhelmed by events and out of touch with the American psyche.

With this in mind, Carter’s private pollster, Patrick Caddell, later acknowledged two things about the 1980 re-election campaign:

- The American people no longer wanted Carter as president, so it would be critical to avoid framing the election as a referendum on his first term. Instead, they needed to make it about the other guy.

- Reagan was their preferred opponent. He would, they believed, be the easiest to beat.

Democrats who’d experienced Reagan first-hand during his years as California governor warned the Carter campaign about underestimating his political talent – “one hell of an effective campaigner who doesn’t rattle and who does well in appearances.” But Carter’s people weren’t convinced.

Accordingly, Carter opted to run against the caricature: Reagan was dangerous and apt to precipitate World War Three. He was ignorant, belligerent, trigger-happy, and imbued with a simplistic worldview derived from his days playing cowboys in the movies.

Early 1980 polling seemed to validate the Carter strategy.

At the beginning of February, Gallup had him beating Reagan by 27 points, and ABC-Harris rated it at 64 to 32 in Carter’s favour. Reagan became more competitive as winter turned to spring before vaulting into a commanding lead following the successful Republican convention in July. However, it was back to a very close race by Labour Day.

The word was that Carter looked forward to debating on television, assuming that his superior mastery of detail would give him the edge. Nonetheless, he took a pass on the fall campaign’s first debate. His reasons were tactical.

A liberal Republican congressman, John Anderson, was mounting an independent third-party campaign and the Carter people felt he was appealing to voters that would otherwise be theirs. So, rather than risk enhancing Anderson’s credibility, Carter sat out the Sept. 21 debate. And when Anderson’s polling numbers subsequently started to drop, the deck was cleared for a Carter-Reagan head-to-head on Oct. 28, just a week before Election Day.

Having seen Reagan in action during the earlier Republican debates, Caddell was opposed to Carter’s participation. He later put it this way: “We were intensifying the fear and doubts about Governor Reagan to an extreme, and the one thing Governor Reagan does not look like on television in a debate is an extremist or a dangerous person. His demeanour is not such.”

Caddell’s fears were justified. The debate went ahead and Reagan’s numbers went up.

Still, the final public polling pointed to a squeaker. ABC-Harris had Reagan ahead by five points, CBS-New York Times had him up by one, and Gallup by three.

On Election Day, though, it was a blowout. Reagan won by almost 10 points, carrying 44 of the 50 states. Election night coverage was devoid of tension, with NBC calling it by 8:15 pm EST while polls were still open in the West.

The scope of Carter’s electoral repudiation can also be grasped by looking at individual states.

After winning Florida by five in 1976, he lost by 17 in 1980, a swing of 22 points; in Texas, the swing was 17; in North Carolina, it was 13; and in hitherto solidly Democratic Massachusetts, it was 16!

Jimmy Carter had come to Washington with high hopes and ostensibly noble aspirations. But after four years, Americans concluded he wasn’t the man for the job and thus declined to renew his contract.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

Explore more on U.S. politics

Troy Media is committed to empowering Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in building an informed and engaged public by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections, enriches national conversations, and helps Canadians learn from and understand each other better.