Why does the Summary diverge so greatly from the full TRC report?

By Rodney Clifton

and Mark DeWolf

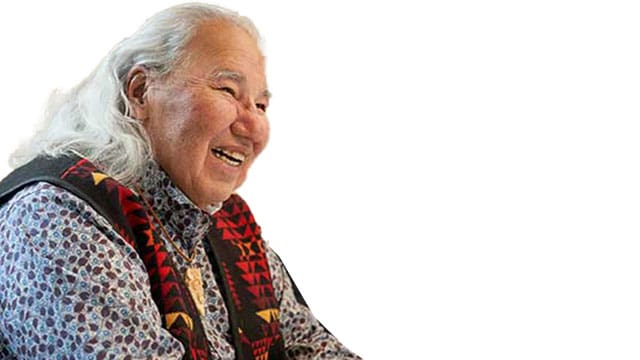

Murray Sinclair, who passed away in Winnipeg on Nov. 4, 2024, left an indelible mark on Canada as a senator, judge, and chief commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). His work highlighted the lasting impact of the Indian Residential School (IRS) system and helped shape Canada’s reconciliation efforts.

However, while many tributes in mainstream media celebrated Sinclair’s contributions, it’s important to reflect on aspects of the TRC’s report that remain contentious and unresolved.

Clifton Rodney |

Mark DeWolf |

The TRC’s work was monumental, culminating in a $60-million report published in 2015. It spanned seven volumes and over 3,500 pages, but some critical issues deserve scrutiny. One significant concern raised by scholars with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy is the failure of the 382-page Summary volume to adequately reflect the findings of the other volumes. Since many Canadians, including journalists, have read only the Summary, this has led to a skewed understanding of the report.

For example, Volume One of the report claims the goal of residential schools was to “terminate the Treaties; and through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal people to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada.” This statement, presented as fact rather than hypothesis, lacks the evidence necessary to support such a grave accusation. Its framing has contributed to the frequent repetition of emotionally charged claims in the media.

The report also characterizes the residential schools’ impact as “cultural genocide,” a term that has since morphed into accusations of actual genocide. This is a controversial assertion. If the intent was to eliminate Indigenous peoples as a distinct group, why did the government sign treaties, establish reserves, publish dictionaries in Indigenous languages, and refrain from banning the use of Indigenous languages in schools or elsewhere? These contradictions were not explored in detail.

In 2021, the Frontier Centre published the first edition of From Truth Comes Reconciliation: An Assessment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report. The second edition, which includes updates reflecting Canada in 2024, was released a day after Sinclair’s death. The book aims to build on the TRC’s work while addressing gaps and inconsistencies. As noted in its dedication, “[The TRC] will provide Canadians with a permanent record that weaves all experiences, all perspectives into a fabric of truth.” The effort that went into the TRC’s data collection is deeply appreciated.

However, key aspects of the report remain unexamined. The TRC did not clearly state that only about one-third of Indigenous children attended residential schools during the system’s 113-year history, and many of those attended for only a few years. It also failed to distinguish between students who remained at the schools for extended periods and those who returned home on weekends or holidays. This distinction is significant, given the emphasis on the harm caused by family separation.

Additionally, the report did not examine whether residential schools managed by different Christian denominations varied in their treatment of students. Were Roman Catholic, Anglican, United, Mennonite and Baptist schools equally harsh or respectful in their practices? A detailed comparison could have provided a more nuanced understanding of the system’s effects.

There are also questions surrounding Sinclair’s public estimate that as many as 25,000 students died while attending residential schools, despite the TRC reporting fewer than 4,000 deaths. The inclusion of a single unverified claim of murder by Doris Young, a relative of Sinclair, further complicates the report’s narrative.

Despite these critiques, Sinclair’s legacy remains profound. His work brought Canada’s attention to the dark history of residential schools and started vital conversations about reconciliation. The Frontier Centre’s 50-page Summary of the TRC report, compiled without government funding, seeks to complement this work by addressing its limitations and encouraging informed debate.

Murray Sinclair did not live to see reconciliation fully realized in Canada, but his efforts laid the foundation for ongoing dialogue. His contributions will continue to inspire those striving for a deeper understanding of truth and justice in the reconciliation process. May his legacy be honoured with thoughtful reflection and continued efforts toward reconciliation.

Rodney A. Clifton is a professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. During the summer of 1966, he was a student intern at the Siksika First Nation Agency Office and lived in Old Sun, the Anglican Residential School. During the 1966-67 school year, he was the Senior Boys’ Supervisor in Stringer Hall, the Anglican residence in Inuvik. Mark DeWolf, a former but non-Indigenous IRS student for nearly six years, is a retired educator. They are the authors of the 2nd edition of From Truth Comes Reconciliation: An Assessment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report,

Explore more on Residential schools, Aboriginal reconciliation, Aboriginal politics

The views, opinions, and positions expressed by our columnists and contributors are solely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is committed to empowering Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in building an informed and engaged public by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections, enriches national conversations, and helps Canadians learn from and understand each other better.